Indonesia is a tough destination to match — seventeen thousand islands, three hundred indigenous tribes, 260 million residents and more than seven hundred native languages.

How about the world’s largest Buddhist temple, fascinating native wildlife and 127 active volcanoes — many of which can be climbed.

White sand beaches, top-notch surfing, world-class scuba diving, friendly citizens and an intriguing history pique your interest? There’s even an acidic lake so corrosive it will dissolve metal.

Indonesia sees just a shade under thirteen million visitors annually, but more than half — nearly seven million foreigners — never set foot off the island of Bali.

Their loss is your gain. The rest of Indonesia is truly spectacular.

But where to begin? So many choices.

How about a trip into the rainforests of Borneo to see our closest primate relative, the orangutan, up close and personal?

Hop aboard a traditional Indonesian klotok and let’s go.

TANJUNG PUTING NATIONAL PARK

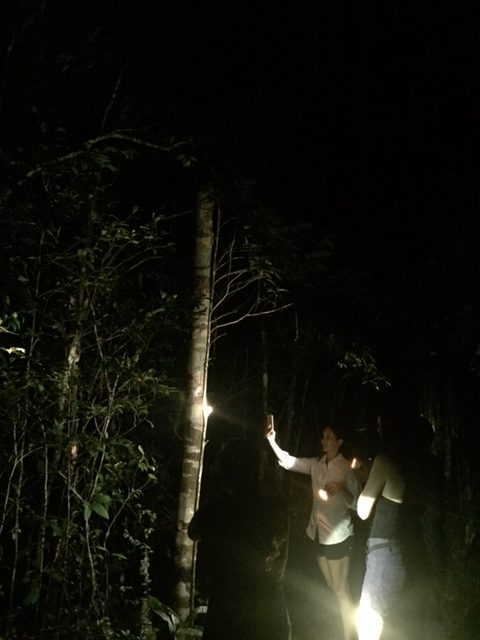

The reaction was like a bolt of lightning; the elusive Western Tarsier had been spotted and everyone knew time was of the essence.

Abandoning the candlelit dinner laid out on the table we hopped to our feet, scooted down the steps at the bow and jumped across to the pier. We scurried over the wooden dock to the sandy path. From there we danced atop prickly ground cover to the edge of the rainforest.

We hurdled fallen trees and ducked low hanging branches, snapping plant life with each step deeper into the rainforest. I absorbed a few scrapes, a couple pokes and only fell once… not bad considering I was barefoot.

Arif and his spotter kept their eyes peeled as their spotlights attempted to keep up with the little critter as it sprang deftly from tree to tree. The guys were pointing out the Tarsier’s movements, but through the dense forest none of us would-be explorers could see a thing.

I peered through a picket fence line of tree trunks, my bare feet balancing simultaneously on broken branches and slippery leaves. I strained my eyes to observe even the slightest movement off in the distance. Adrenaline coursed through my body.

“I see it!”, someone chimed in excitedly.

“Right there! Over that branch, next to that tree… follow my arm… see it?!”

Arif spent the better part of three years working at this very spot and despite the time commitment only saw the tiny creature on a handful of occasions. He was understandably excited and wanted us to share in the moment.

“Oh yeah, there it is! Right there… it just hopped onto that big tree!”

I still couldn’t see anything.

TARSIUS BANCANUS

Everyone’s eyes were laser focused on the Tarsier at this point.

I craned my neck, bobbed my head and angled for the best possible view of the object of their fascination.

And then I saw it!

The Tarsier clung to a tree with its tiny forelimbs. Its super-sized eyes, evolved for a nocturnal lifestyle, lit up in the reflected light. Its head spun nearly three hundred and sixty degrees! Then it sprang several meters through the thick jungle air to the next tree.

In short order the little guy was off, deeper into the jungle in search of a meal. We retraced our steps in the opposite direction, an evening meal on our agenda as well.

It was a thrilling end to an amazing day in Tanjung Puting National Park.

Now, on an environmental endorphin high, back to that candlelit dinner…

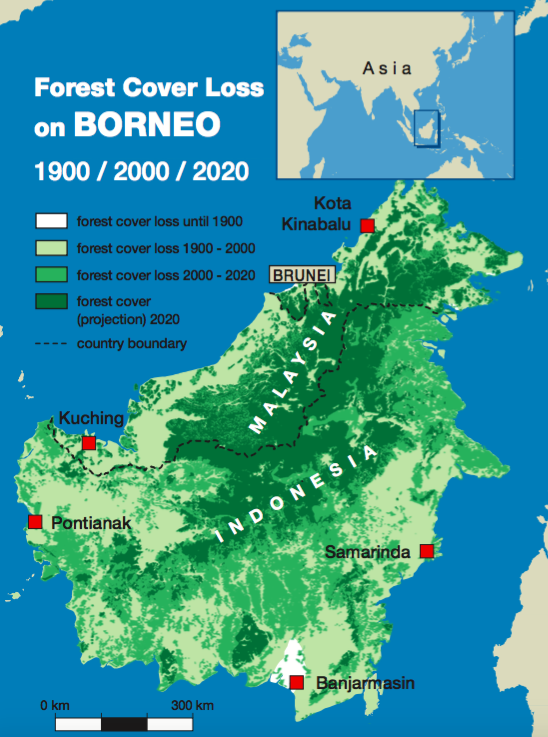

BORNEO

Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia share the island of Borneo. Indonesians call the entire thing Kalimantan.

Speaking of lands the British tried to colonize, check out my experience in the former capital of British Burma

As a kid I associated Borneo with pristine wilderness, impenetrable rainforests and cool animals. In my mind the place was basically one giant PBS episode of Nature.

Then I began researching and planning my visit. I discovered the modern-day truths about Borneo. Illegal logging is rampant, deforestation continues at breakneck speed and environmental degradation is a life threatening issue.

The bullet point list of Borneo’s present ills makes for a sad read.

By some estimates, logging or burning felled up to half of Kalimantan’s lowland rainforest over the past thirty years. Teak, ironwood, ebony and sandalwood make their way out — up to 70% illegally — while palm oil plantations move in. Deforestation leads to soil erosion and the spoiling of jungle rivers.

Local communities and wildlife alike suffer the consequences.

Borneo’s endangered wildlife list includes the pygmy elephant, Asian two-horned rhino, orangutan and clouded leopard. Orangutans have lost almost ninety percent of their native habitat due to palm oil-based deforestation and become targets when they’re forced out in search of food.

Sounds like a complete disaster, doesn’t it?

Before shaking our heads and pointing fingers, let’s keep something in mind — Indonesia’s populace is relatively poor. Can we blame a poverty-stricken community for prioritizing dinner and their child’s wellbeing over a stand of trees or a few endangered animals?

As awful as the situation appears on the surface, it’s not all doom and gloom. Hearts and minds are changing. Locals are seeing long-term benefits in the future of eco-tourism and responsible development.

Borneo is the world’s third-largest island, trailing only Greenland and another regional heavyweight, New Guinea. At 743,000 km² (287,000 mi²), it’s about ten percent larger than the state of Texas. Pretty amazing that even after all the logging, mining and burning Kalimantan remains the world’s 3rd-largest stand of tropical rainforest.

KALIMANTAN

The Tarsier sighting was awesome, but the focus of my visit to Borneo was to see the endangered orangutan, current habitat reduced to just two of Indonesia’s thirteen-thousand plus islands. Doing so meant chartering a local boat — a klotok — to take me up the Sekonyer River, deep into the jungle where the “Person of the Forest” resides.

My Trigana Air flight from Jakarta was almost entirely full of local men. Almost. Besides me there was one white girl aboard.

Southern Kalimantan isn’t exactly a hotbed of independent tourist activity, so I correctly assumed Brittany and I would be spending the next few days together.

A friendly gentleman met us at the tiny airport in Pangkalan Bun, bundled us into a car and drove us to the dock in nearby Kumai. Our next mode of transportation awaited.

Two hours prior we sat in the traffic-choked capital, exhaust polluting the air and hanging around the city like an uninvited guest. And now we motored through Borneo’s waterways in a speedboat, sun beating down, water spraying, civilization quickly vanishing in the distance.

I couldn’t stop smiling.

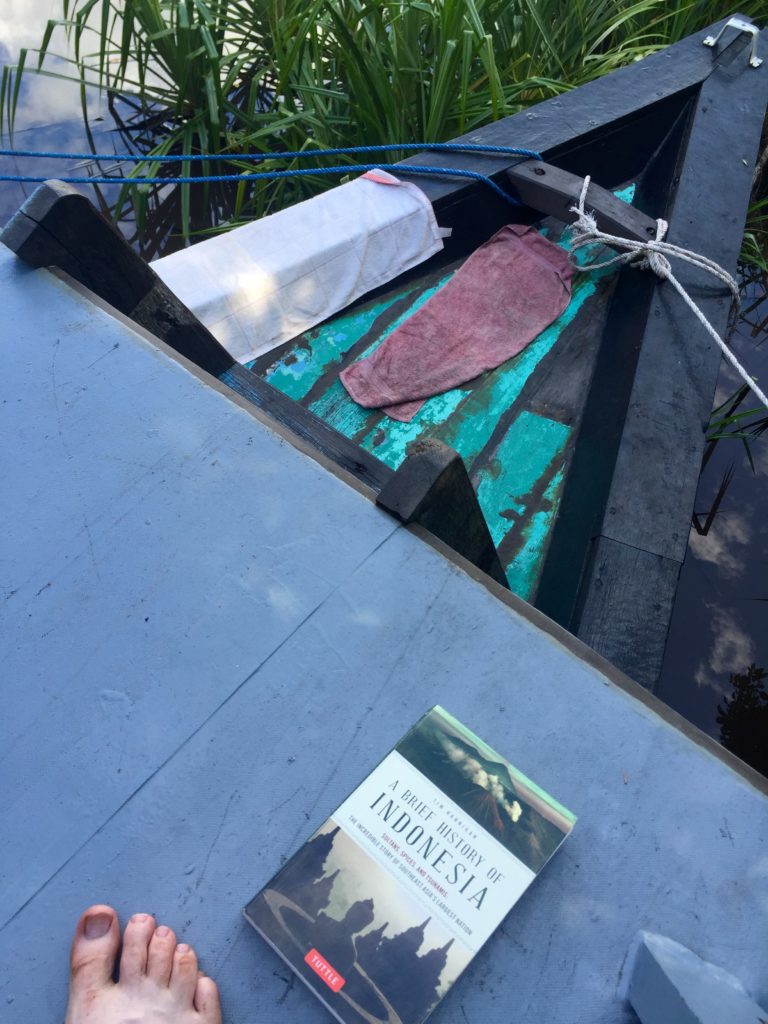

THE KELIMUTU KLOTOK

About twenty minutes after setting off, the speedboat pulled up alongside a rather impressive looking wooden vessel. It had two main decks, a roof and an elevated back deck. The boat looked brand new! A blue placard hung from the side — Kelimutu. I handed my backpack across to a smiling young man and climbed aboard.

Independent travelers from Germany and China rounded out our five-some, one-eighth of the forty visitors in a park the size of Rhode Island.

A lovely married couple, Dessy and Arif oversaw the entire Kelimutu klotok operation. I discovered their company, Orangutan Applause, while researching my options a couple of months prior. Their website and #1 Trip Advisor reviews said it all — passionate, responsible, friendly.

Dessy and I bonded straight away — I owed her a major debt of gratitude. She basically arranged my entire trip. We swapped numerous emails with different date possibilities and arrangements. I’m alone, but don’t want a solo boat trip through Kalimantan. Got it! I land on this date, could also do that date and prefer a three-night trip. Done! Is it possible to fly to Yogyakarta afterward? No problem!

She is one amazing woman.

Dessy is the wizard on the backend while Arif handles most of the guiding. He is a qualified biologist, sports an impressive resume of eco credentials and has a passion for the local environment I could hardly believe.

Exceptionally capable hands indeed.

The Kelimutu wasn’t half bad either. A cozy clean water shower sat opposite the bucket flush toilet on the lower deck. The bow offered a Titanic-like king-of-the-world view while the elevated back deck allowed unobstructed sight lines of the entire area.

KLOTOK LIFE

We alternately lounged on the back deck of the klotok, perusing books on Indonesian history and calling out wildlife for the others to see. We peered into the water as the klotok glided along, hopeful for a glimpse of the crocodiles which infest the rivers and kill unfortunate locals and visitors on an annual basis.

Meals were taken on the top deck. Proper lunches, a variety of snacks and vegetarian-friendly dinners rounded out our culinary days.

After dinner the crew laid out mattresses near the bow and unfurled mosquito nets. The roof held back roll-down tarps which enclosed the main deck in case of foul weather. We slept and woke with nature’s rhythm, falling asleep to the sounds of the rainforest and rising with the sun.

5:30AM doesn’t hit nearly as hard when views from bed include the Indonesian rainforest. And life ranks pretty good when Proboscis monkeys provide the soundtrack to an open-air breakfast.

BIRUTE GALDIKAS

Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey — world-famous, right? Both are well-known for their groundbreaking research work with chimpanzees and mountain gorillas in Africa.

But how about Biruté Galdikas? I’ll venture a guess you’ve never heard the name. Until recently I had never heard of her either. And I’m not sure why.

Arif joked I should ask her myself. Funny guy, that Arif. But I’m legitimately curious why she is almost unknown yet the others are conservation and primate world superstars.

Galdikas is the third member of the “Trimates”, a trio of female researchers backed by famous anthropologist Dr. Louis Leakey. While Fossey and Goodall toiled in Africa, Galdikas and her husband shipped off for the rainforests of Kalimantan.

CAMP LEAKEY

In 1971 the duo set up a primitive jungle base near Borneo’s Java Sea coast. It was christened Camp Leakey.

Three main goals inspired the camp’s founding —

- Care for, rehabilitate and release orangutans from the commercial pet trade

- Educate local communities and authorities

- Create and increase tourism in order to maintain long-term orangutan viability

By all measures, Camp Leakey has been a rousing success. 1975 saw a cover story in National Geographic. In 1982 the surrounding reserve was declared Tanjung Puting National Park. The camp has grown from humble beginnings and hosts an array of staff, scientists and researchers. Travelers too. We stopped by one morning for a look at dusty exhibits, maps and old photos.

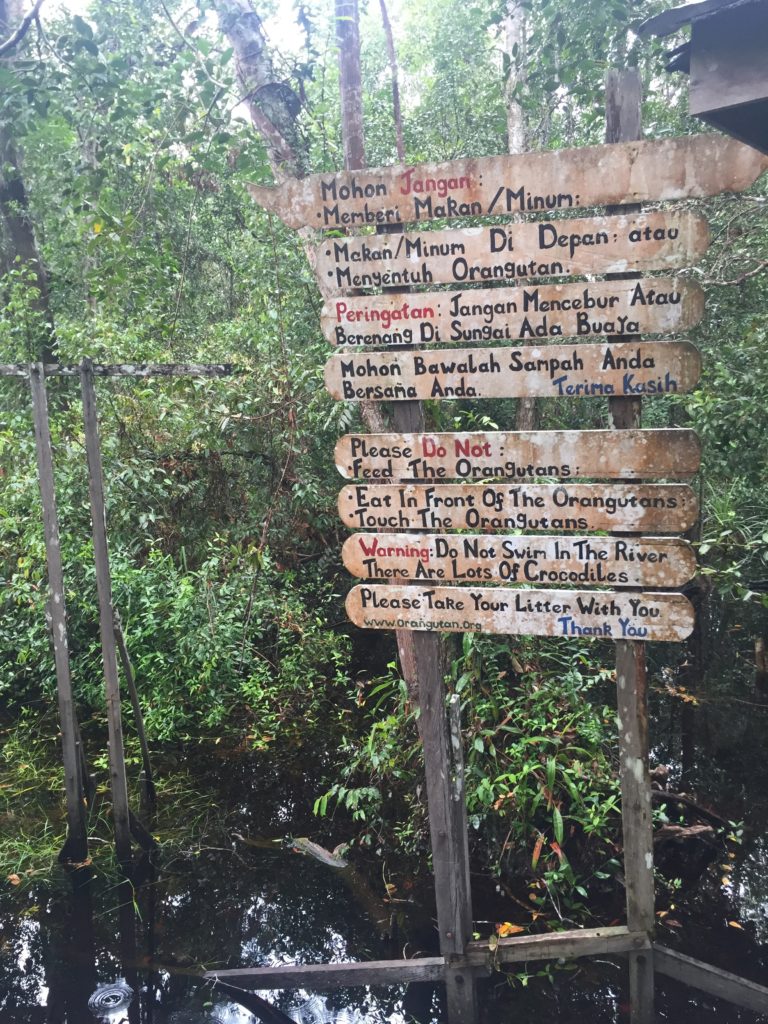

After visiting camp we made our way to one of the feeding stations in the surrounding national park.

Wait, what? Feeding stations?!

I’ve heard people criticize this experience as fake, not wild or artificial. Nothing could be further from the truth.

To understand the necessity of such “unnatural” feeding stations, appreciate the following — orangutans share 97% of their DNA with humans and spend the first seven years of their lives by their mother’s side. Now consider an orphaned human baby. Orphaned orangutans require the same special attention. It’s easy to mess up their care. The orangutan rehabilitation and release process is highly complex and requires a massive time investment.

THE PERSON OF THE FOREST

“Whooooooooo!”

We were walking single file into the rainforest when the first calls went up.

“Whoooo! Whooooooooooooooooooooo!”

I heard plenty of “Who’s” over four days and smiled every single time.

But to a rehabbed and released orangutan, this call meant one thing — snack time.

Park staff haul bananas, melons and milk to small jungle clearings where semi-permanent bamboo platforms have been set up. The food is purely supplemental. In no way does it replace the wild foraging orangutans engage in in the ‘real world’.

More often than not a group of orangutans arrive for a feed. There are mothers with babies and solitary males with distinctive cheek pads, young ones and old ones. Wild pigs show up. Gibbons sneak in for a stray banana or three.

Orangutans are funny animals. A baby orangutan appears to be going bald, but sits on its bum and peels bananas like a human baby. Cuteness overload. Then it looks at you with the vulnerable innocence of a creature entirely dependent on its nearby mother… my heart turned to mush.

Light filtered through the canopy. Trees rustled in the distance as a solitary primate headed our way. But it wasn’t an orangutan. This thing had crazy long arms and swung through the trees with impressive ease. It was a gibbon. That cheeky gibbon dropped down fire pole style and managed to steal a handful of bananas from the bamboo platform.

How awesome is this?!

I leaned back on a wooden bench, closed my eyes, took a deep breath and soaked in the experience.

FAREWELL, KALIMANTAN

One of China’s most famous wildlife photographers joined my trip. He was keen on taking time for top-notch photos and no one else seemed interested in rushing. Ruci didn’t have the same pricey equipment as her Chinese compatriot, but snapped stunning photos regardless. She took several of the high-quality wildlife photos in this post. The German? Utterly prepared, as usual — lenses, filters, you name it. But she didn’t bring malaria pills! A most surprising oversight. And the Americans? Well, we had iPhones to enhance our memories.

We walked down sandy paths, through knee-high grass and over muddy tracks. Back on the wooden boardwalk Dessy called us to a halt. A lone orangutan sat on the elevated path in the distance. Orangutans have full right-of-way around here, so everyone knew to stand quietly still.

After a moment’s thought the primate began knuckle-walking in our direction. He stuck to the far edge of the planks and stopped right next to me. I could have low-fived him. He took a quick look around, inspected our group, scratched his face and carried on.

As he walked back toward the jungle everyone turned around for a look.

So did he.

Check out the orangutan walking past us in this mobile phone clip

DO IT YOURSELF

Getting There

To see the orangutans of Tanjung Puting National Park you’ll first need to fly into Pangkalan Bun (PKN). You have a few choices.

Jakarta (CGK) — I flew non-stop on Trigana (925a). NAM Air (640a) is the other non-stop option.

Surabaya (SUB) — Trigana (610a) is your best bet, although NAM flies this route in the afternoon (130p). The late arrival messes up daytime plans and necessitates an overnight stay.

Semarang (SRG) — NAM (620a, 1000a and 205p), Trigana (1235p) or Wings Air (1p). Semarang is a few hours by bus from Yogyakarta. I flew here with Ruci after the klotok trip and continued my travels in Yogyakarta. Her Bahasa Indonesian language skills smoothed the way, but you will manage without.

Yogyakarta/Bali/Everywhere Else — Connections required. Google flights will sort you out.

Note — Flights in and out of Pangkalan Bun are regularly delayed or cancelled. Flying out for an immediate international connection is playing with fire. Plan carefully.

Sleeping and Eating

I spent my entire trip on the klotok, but land-based possibilities exist. A few accommodation options are in the park’s vicinity, but by Indonesian standards can be expensive. Rimba Eco Lodge falls into that category. A speedboat transfer from Pangkalan Bun to the lodge will set you back US$27.

No matter where you stay, a boat trip to experience the natural environment and see the orangutans is a requirement. Excursions can be planned through your accommodation or combination deals can be arranged — two nights on land plus two nights on a klotok, for example.

Multi-day klotok trips visit areas deeper in the rainforest which are inaccessible to day trippers. In my mind that’s a big benefit to boating your way around the park.

All things considered, I felt the klotok trip ticked all the boxes.

Seeing the Sights

I cannot recommend Orangutan Applause highly enough. Guiding is top-notch. Booking and communication couldn’t have been better. Their klotok is absolutely beautiful. Transfers work seamlessly. Dessy and Arif have it dialed in. They are also kindhearted, genuine people trying to educate their guests while supporting a growing family.

Dessy and Arif are working on a homestay option as well, so keep them in mind while researching your options.

Klotok trips are generally flexible. I spent three nights on board while one guest had other plans and departed after two. Considering the fly-in fly-out nature of a trip, I would say three nights should be a minimum. On the other hand, the experience is so cool it may be worth squeezing it in to a larger plan. Depends on your travel style.

Booking on location in Pangkalan Bun is also a possibility. I enjoy researching trips and would rather pay a few extra dollars for the privilege of knowing the operator and plan in advance.

Klotoks run year-round. Peak travel season is March through May, but also coincides with increased rainfall. Rainfall also ramps up in November/December. Best weather — June, July and August. I visited in June; minimal rain, tolerable humidity.

Costs

Overnight klotok trips run in the neighborhood of US$125/per night, per person.

Typically when booking ahead you will make an online down payment — possibly via PayPal — before settling up in person with Indonesian rupiah. This is standard practice, but do your research before sending money around the globe!

Note — If you book a trip to see Kalimantan’s orangutans, please book direct with the local operator. Travel agencies may be able to do some leg work on your behalf, but booking direct puts more money into local hands. That is the single best way to ensure local communities benefit from increased visitation and that tourism of the responsible, sustainable type carries the day.

Tips

Malaria — Prophylaxis is highly recommended. Going without is asking for trouble. All of Borneo is a malaria zone.

Dengue fever — Take it from someone who was infected, hospitalized and flat on his back for weeks; Dengue fever is no joke. Read up.

Bring mosquito repellant, wear long pants/sleeves when mosquitoes are most active — early evening. Make sure you have close-toed shoes for trips into the rainforest.

Pingback: My Battle with Dengue Fever in Indonesia | No Guidebooks