This is a rather lengthy piece detailing my experience with dengue fever in Indonesia. It includes the days preceding my eventual diagnosis (woozy volcano hike included), subsequent treatment and lingering long-term effects.

If you’re here in search of information on dengue fever and would rather skip the details and backstory, feel free to click here and jump ahead to the specifics.

——————

I had been flat on my back for the better part of twenty-four hours, sleeping in fits and starts, randomly roused and annoyed by the excessively loud calls to prayer from the nearby mosque. I had a fever, my body ached. Something definitely wasn’t right.

I thought I had the flu.

But I traveled halfway around the world to see the famous blue flame at the sulphur mine on Kawah Ijen.

Flu or no flu, I was determined to give it a go.

In hindsight this probably was not the best decision, but at the time — after a full day of resting up, taking paracetamol tablets and vitamin B pills, drinking powdered Gatorade — it seemed perfectly reasonable.

At 1230am on a muggy Thursday morning I piled into the back of an SUV with a local guide/miner and two other travelers for the experience of a lifetime. The windy drive up from Banyuwangi, my base at the eastern tip of the island of Java, would take about an hour.

KAWAH IJEN

Indonesia is home to one-third of the world’s active volcanoes, but Kawah Ijen is especially noteworthy due to the unique phenomenon of sulfuric gas combustion which occurs on its slopes. The gases emanate from cracks under extreme pressure and at high temperature — up to 1112 degrees Fahrenheit. When the gases contact open air they ignite, flames shooting sixteen feet in the air. Some of the gas liquefies and flows down the slopes with the appearance of blue lava.

The “Blue Flame” is the reason I came to this part of Indonesia.

After a quick detour to Indomaret for Snickers bars and bottled water we pulled in to the rather busy parking lot at the base of the nine thousand two hundred foot Ijen. I hadn’t taken more than twenty consecutive steps all day and it quickly became apparent this hike was going to be an ordeal.

To the Blue Flame we go

The crater rim sat 1.8 miles (3km) up from the base, the mine area a half mile descent beyond. A technicolor lake corrosive enough to dissolve metal acted as the mine’s beautifully poisonous backdrop.

A spectacular full moon and stars more prominent than I had seen anywhere outside the Australian Outback illuminated the pitch dark sky and lit the way. It was a strikingly beautiful scene. On a normal evening this hike would be nothing more than a pleasant stroll, but tonight I was struggling.

I managed the first kilometer in decent shape, tired but keeping it together. Then the slope quickly increased and my ailment became obvious. Sweat rapidly drenched my clothes and I was continually short of breath.

I simply couldn’t keep up.

My trip mates forged ahead and Gin, our guide, stuck with me at the back.

By the rest stop two kilometers from the start, I was gassed. I sprawled out against a wooden shack which boiled up hot coffee and tea for my fellow adventurers and tried to catch my breath. I re-calibrated and set my new goal as the rim, a thousand meters ahead.

Gin called the next stretch “two hundred up, eight hundred flat”. My energy meter read virtually zero, but Gin’s comment buoyed my flagging spirits. Even in my weakened state, I thought two hundred meters were manageable. At least I could see the crater from that point, I reasoned.

Turning back

By this point the increasing pressure in my head was becoming a major problem. I could barely maintain an upright position, let alone physical exertion. I hardly felt like myself.

After an extra long rest I hauled my body out of the dirt. I trudged slowly up the slope, one foot in front of the other, barely looking up from the ground at my feet. My Canadian and French companions went ahead while Gin puttered along at my pace.

The path wound steeply up from the shack as my progress nearly ground to a halt.

After less than fifty feet I began to cough, a deep, guttural cough which roused my stomach. I stopped as it continued, then vomited into the dirt. The contents of my stomach emptied onto the path as I fell to my knees. On my knees in the dirt, spitting vomit from my mouth, I knew Ijen wasn’t happening.

Gin rubbed my neck as I considered the arc of my entire trip, the planning, the anticipation, the disappointment. I envisioned the lake above, high levels of hydrochloric acid turning the water a spectacular shade of turquoise and contrasting wonderfully with the black sky. The jealously toward every pair of feet that plodded past while I sat in the dust was palpable.

Devil’s Gold

Miners carved out a living at Ijen hauling 170 pound (77 kg) loads of sulphur out on their backs, literally poisoning themselves to an early death. Bringing home two to three times the average local daily wage (between US$5 and $12) makes their surreal, hellish job worth the inherent risks.

What exactly do we use mined sulphur for these days, you ask? Ninety-five percent of the sulphur mined at Kawah Ijen is used in the processing of sugar.

Unexpected, eh?

Safety precautions were… let’s just say Ijen wouldn’t pass muster in most Western nations. A few miners carried proper gas masks, but a majority of the local men simply wrapped a dampened cloth around their face and left eyes exposed to the noxious gas.

Not surprisingly, their average life expectancy was just forty-seven years.

Unlike some of the miners, I carried a full gas mask in my backpack. Had I managed to reach the lake I could at least prevent the toxic fumes from burning my lungs. But now my only concern was getting out of here.

The group carried on without me and wouldn’t be back until after sunrise. It was only 3am, so I had the temporary luxury of sitting on my rear end at the shack until I felt like moving again.

The chilly breeze eventually drove my sweat-soaked clothes and I back down Ijen’s slopes. On the way I declined repeated offers from entrepreneurial locals providing lifts on wooden hand carts and homemade stretchers. I stumbled down on my own, doing my best to mime stomach and head issues for those curious at my surprisingly early presence.

I was literally the only person walking downhill.

Once in the parking lot I tracked down our vehicle, woke the napping driver and slipped into the back seat. I curled up with my grandmother’s scarf and tried to sleep.

Another outdoor adventure, this time In search of orangutans in Borneo’s glorious Tanjung Puting National Park

By 7am the parking lot was buzzing with folks whose wide smiles were indicative of the wonders they had just witnessed. My trip mates offered to show me a few of their undoubtedly awesome photos, but I couldn’t muster much interest. I was equal parts ill and disgusted that I didn’t get to see Ijen’s sulphur mine and blue lava with my own eyes. I sat in the back as we started on the journey to Banyuwangi, tied a scarf around my eyes and tried to avoid throwing up.

Do I Have Dengue fever?

By this point I feared I might have dengue fever.

I spent long stretches of the previous day in bed Googling odd tropical illnesses and dengue seemed the most likely culprit.

Delaying treatment could lead to the deadly hemorrhagic fever, internal bleeding, shock, even death. I wasn’t sure which version I had, but I definitely didn’t want to leave it to chance.

Banyuwangi had a hospital that contracted with my travel insurance provider, but I wasn’t too keen on calling in there. Bali was the place for international quality medical care. But how to get there? The island itself was just a short ferry ride away, but the main city of Denpasar and the better medical facilities were almost four additional hours by road. I arrived in that fashion a few days earlier, but couldn’t imagine the reverse journey in my current state.

Since finishing the Ijen hike, the pain in my joints had ramped up considerably. My head felt like it could spontaneously combust at any moment. Just thinking straight had become a considerable chore.

It seemed I was getting worse by the hour.

I was fully prepared to hire a expensive taxi to shuttle me to the hospital, but the fantastic guesthouse manager made some calls and arranged for a shared minibus to drop me at the hospital of my choice in Denpasar.

I gingerly made my way back to my room and gathered up my belongings. Packing and carrying my backpack required a colossal effort which caused intense pain in my hands. My elbows, wrists and knees were all throbbing with pain too, but the sheer number of joints in my hands made them the focus of my physical discomfort.

Seems dengue’s ‘break bone fever’ nickname was no joke.

The minibus arrived in short order. I thanked the manager profusely, took a seat in the back, covered my head with a scarf and zoned out. After making a few stops around town, we boarded the drive-on ferry. I slowly made my way up to the passenger cabin and laid down on a bench.

Back to Bali on the Highway to Hell

Forty minutes and one relatively smooth crossing later we were back on the road, fighting the horrendous Balinese traffic.

Start. Stop. Move fifty feet. Jerk to a halt.

Car horn blares.

Accelerate quickly. Brake hard. Stop.

Repeat.

Repeatedly.

I shared a three seat bench in the last row with a single Indonesian man. Bless his kind heart, he could tell I was in an awful state and allowed me to lay my upper half across two of the three seats.

Every so often I picked my head up, fumbled through my pack and managed to slurp down what felt like an eyedropper full of water. I felt lucky to keep that down. My stomach began to growl, but eating was out of the question.

Laying down felt infinitely better than sitting up, though the incessant herky-jerky movement of the minibus made me feel like I was losing my mind — not to mention my stomach.

But I did manage bits of on and off sleep.

I woke from one of my restless naps to find the sky dark. I looked at my watch.

The normal four-and-a-half hour trip had morphed into a seven hour test of my sanity.

The entire afternoon had faded away in a hazy mix of seasickness, dry cotton mouth, pounding headaches and achy joints.

Chills consumed my entire body while a clammy sweat broke out on my forehead and my hands trembled involuntarily.

I didn’t know how much more I could tolerate.

We were motoring around the sprawl that is Denpasar, seemingly not making any progress. Half of my fellow passengers had since departed the van, but my hospital stop didn’t appear to be coming up. As if things couldn’t get any more ridiculous, the driver pulled over and stopped. He took an animated phone call and looked over his shoulder out the window.

We sat there for several minutes.

“Siloam!” I broke the silence with the hospital’s name.

He looked my way with the distant stare of a man who could not give less of a shit.

I had enough.

Mustering all my strength, I hauled my backpack over the back seat, opened the door and slipped into the soupy evening air. I dropped my possessions in the nearest driveway, paid the fare and sat down on my backpack. I punched up Uber and ordered a ride to the hospital.

The car’s progress tracked on my phone, but I could tell it wasn’t coming to my precise location.

Seriously?!

It doubled back and forth down the main road, a few hundred meters away, but refused to turn down my street.

WTF IS GOING ON?!

Pretty much the last thing in the world I wanted to do at that moment was load up two backpacks and walk several hundred meters in the Balinese humidity.

But I had no choice.

I made it to the end of the block, totally sapped of energy and drenched in sweat. I felt like I was about to pass out.

Of course my ride drove by again.

SILOAM HOSPITAL DENPASAR

I stumbled into Siloam Hospital shortly after 9pm, nearly ten hours after leaving Banyuwangi.

“Dengue.”

I put my quivering hand to my searing forehead.

A friendly staff member immediately escorted me to the emergency department. We passed through a set of heavy doors, walked by the nurse’s station and made a beeline for an empty bed in the corner. I dropped my backpack on the floor, climbed onto the bed and closed my eyes.

A sense of relief washed over me as tears welled in my eyes.

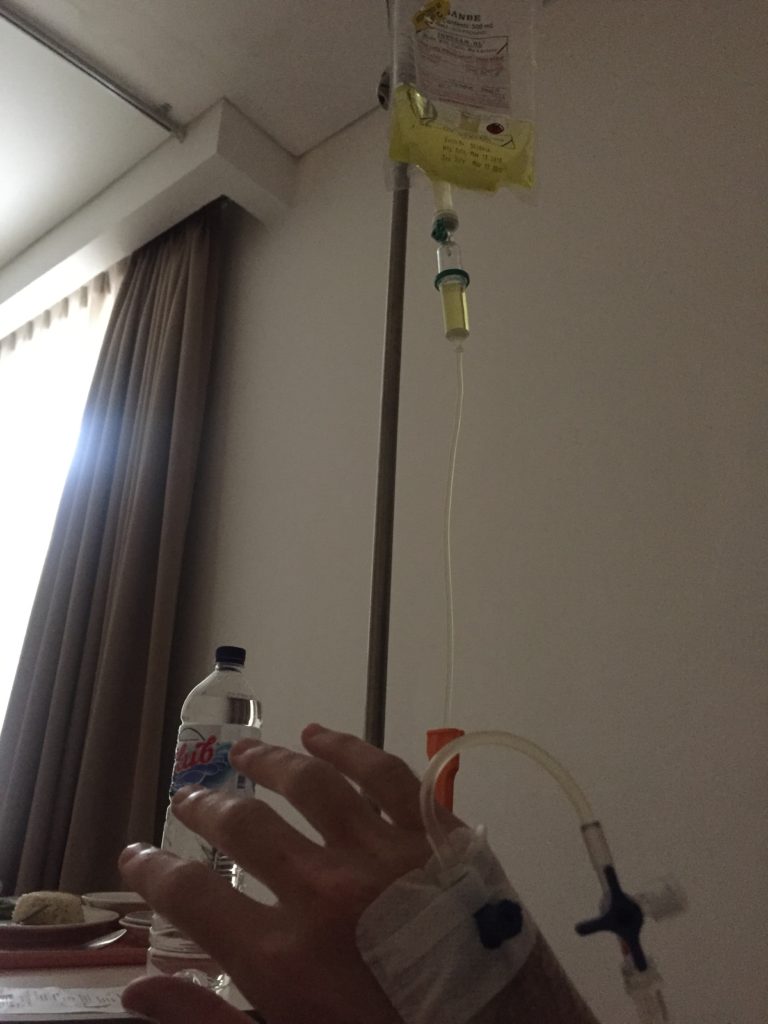

Within minutes I was hooked up to an intravenous drip. Staff took my passport and drew blood. I signed a couple of documents and okayed a deposit on my credit card. A nurse poked my stomach with an anti-nausea injectable. Vitamin shots and liquid paracetamol shots quickly followed.

I laid there, stared at the ceiling and considered my situation.

My entire body ached. Intense arthritis-like pains throbbed in my fingers, wrists and elbows. My knees felt like those of a retired bricklayer.

Fierce waves of chills washed over my entire body. I shivered uncontrollably.

A rather unpleasant force tried to push my eyes from their sockets. My head felt like it had been soaked in gasoline and lit on fire.

I felt nauseous even though I hadn’t eaten anything proper for the better part of 36 hours.

My mouth and throat were parched, my lips dry and cracked. I wanted to guzzle water by the bottle, but feared immediately vomiting.

Basically, I was a mess.

Dengue Inpatient

Some time went by before a heavily accented English-speaking doctor came in for a chat. He didn’t have any definitive news, just that I would be admitted. Beyond my possible tropical disease, I was also severely dehydrated.

At 4am, twenty-eight hours after my attempt on Kawah Ijen, a beautiful Balinese girl in a head scarf wheeled me up to a shared room on the third floor.

I managed a few hours of sleep before the morning shift nurse came in around 7am. She jabbed my stomach with another anti-nausea injection, added a bag of neon green fluid to my drip IV and drew more blood. Bless those anti nausea injections because I actually felt like having breakfast. I took it easy and stuck with fresh fruit and a cup of tea.

I called my parents and filled them in. Dad had already looked up flights and Mom was… rather concerned. As mothers are apt to be, right?

Before lunch I felt the need to do something I hadn’t done since being admitted — use the bathroom. The IV port stuck out on top of my right hand, so I couldn’t just get up any time. Plus I was under orders not to get out of bed unsupervised.

I rang the call bell and waited for a nurse. She temporarily click stopped my IV drip and disconnected the tube from the port.

Then we walked to the bathroom together. Verrrrrry slowly.

It felt like every ounce of my energy had been drained from my body. Never in my life had I felt like this, so weak and utterly exhausted.

I made it back to my bed and flopped down in a heap.

Hospital Life

I shared the room with Jean-Claude, a French-Canadian who wound up on the wrong side of a rogue Balinese wave. He suffered a broken clavicle and spent his time drifting in and out of considerable pain. I felt bad for him and his impending surgery, far from the familiarity of home.

We bonded over our respective predicaments.

Every couple of hours a friendly nurse or aide came in to tend to me; a new IV bag or neon additive, stomach injection, temperature check, meal or snack, fresh bottle of water.

My initial blood panels returned inconclusive results. A low platelet count was the only abnormality. Dengue takes a known course and often requires a few days to prove positive in lab work. Dr. Arthawibawa knew I was sick and had his suspicions. He confidently stated I had either dengue fever or malaria. We would know in a matter of time, but at this point he was certain of one thing — I was not going anywhere.

I cancelled my impending flight home. Pleasant side effect of my illness, that.

And so the next few days passed. Drip bags and stomach injections. All the fresh pineapple and papaya one human being could ever want. Slow walks to the bathroom. A positive dengue diagnosis. Emails to and from my travel insurance provider.

Mostly, though, I just laid in bed. As one does when in hospital, I suppose.

Release

After four days of medical treatment and plenty of rest, Dr. Arthawibawa came in one morning and pronounced me fit for release. Once cratering, my platelet count was on the rise. The nausea disappeared. I no longer felt like I was about to collapse, catch fire or spontaneously combust. The pressure on my eyeballs ceased. My energy increased.

I actually felt pretty good.

I was still infected, but dengue typically sticks to a routine path and the doctor had confidence I was on the upswing. He suggested I check in to a nearby hotel, take it easy for a few days and come back immediately if I felt worse. I was given ten days worth of vitamins and advised to continue with paracetamol for aches and pains.

I took the news of my release to celebrate with my first real shower in over a week. My accommodation in Banyuwangi had a traditional cold-water Indonesian scoop and bucket shower, so this hot water thing was real luxury. And it felt truly wonderful.

I put on normal clothes for the first time in four days and sat upright in a chair.

Sometimes it really is the little things in life.

Discharge

After lunch the nurse came in to delicately remove my IV and the port on top of my sore right hand. I shook Jean-Claude’s good hand, hugged his wife Katy and vowed to cross paths again.

A staff member escorted me downstairs to a bank of administrative workers doing their duty behind a series of desks.

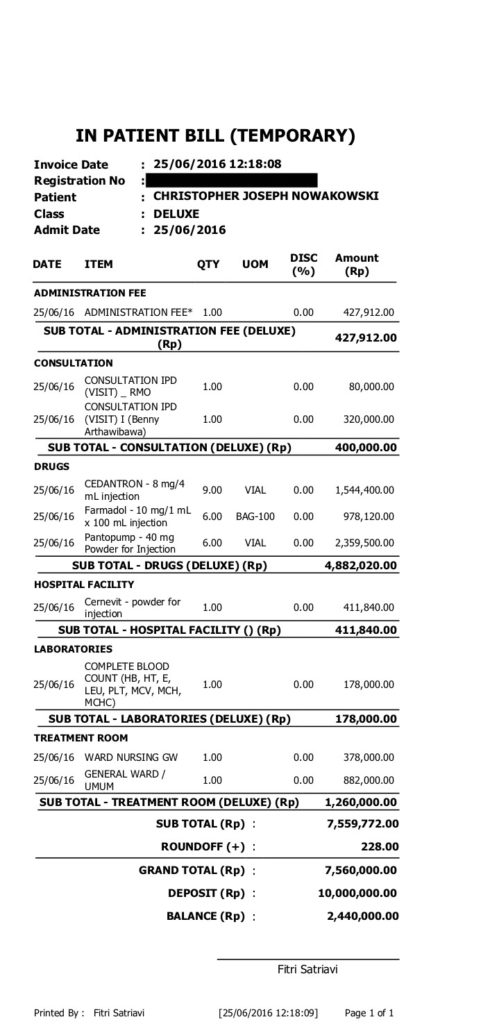

Paperwork and financials were straightforward. The cashier refunded my credit card IDR 8,670,000 (US$652) of the original IDR 10,000,000 (US$752) deposit. My travel insurance folks were on the ball from the start.

Total expenditure on my end? US$38 for the policy plus a US$100 deductible. US$138 total for four days in a quality hospital plus round the clock medical care, numerous blood tests, injections, IV bags and meals, plus an 8-hour stay in the emergency room.

Compare that to the itemized bill from the hospital which ticked up to US$525 for one day, so it seems my comparable stay without insurance could have set me back close to US$2500.

Tough to complain about those financials.

I walked out into the early afternoon sun and hopped in an Uber. Five minutes later I checked in to a hotel in Kuta, perhaps the most touristy spot on the most touristy island in the world. I took a slow walk that afternoon and laughed to myself at the existence of Pizza Hut and Wendy’s, the crowded beach, the constant hawking, the full face of the Balinese tourism industry.

Everything I hoped to avoid in Indonesia was staring me right in the face.

But I was glad to simply be here in recovery mode, the worst of “break bone fever” in my past, a trip home in my future.

Life with Dengue Fever

I re-booked my flights and flew home to the US via Bangkok and Paris a few days later. Originally I planned on going back to work the following Monday, five days after landing.

But that didn’t happen.

Most of my symptoms had improved since departing the hospital, except for the fatigue. I was absolutely exhausted. All day, every day. Walking up a flight of steps wiped me out for hours. I managed grocery shopping and the necessities of daily life, but anything more was simply out of the question.

Running, walking reasonable distances, doing yard work? No, no and, uh, no. I had to pay someone to mow my lawn.

I returned home the first week of July, so the midsummer heat and humidity probably didn’t help my stamina, but it seemed I had zero energy. As in none whatsoever. I felt better upon discharge from the hospital than I did sitting around my air conditioned house.

Just to be safe I called the travel medicine department at the University of Pennsylvania. Wait time for an appointment? Seven weeks! I went to see my family doctor instead. Unsurprisingly, she knew absolutely nothing about dengue fever. I pointed her to the CDC website and filled her in to the best of my ability. Luckily for me, she was kind enough to sign off on paperwork verifying my need for short-term disability.

At the time my job involved overseeing large construction projects and entailed plenty of walking, so there was simply no way I could handle employment. My office actually suggested I look into the benefit. I didn’t think the insurance folks would be keen on paying out for a guy who contracted a tropical disease while backpacking halfway across the globe, but they did!

So I spent the next five weeks hanging around my house, engaged in very little beyond books, television and the internet.

Despite the time off from work and the freedom that afforded, my summer was actually rather depressing.

In early August I returned to work. My long-term lack of energy forced the cancellation of a previously booked September trip through Peru and Bolivia. Instead I went for a less physically demanding holiday in Ireland.

By mid-September, three months after contracting dengue fever, I once again felt like myself.

———————

DENGUE FEVER

The Basics

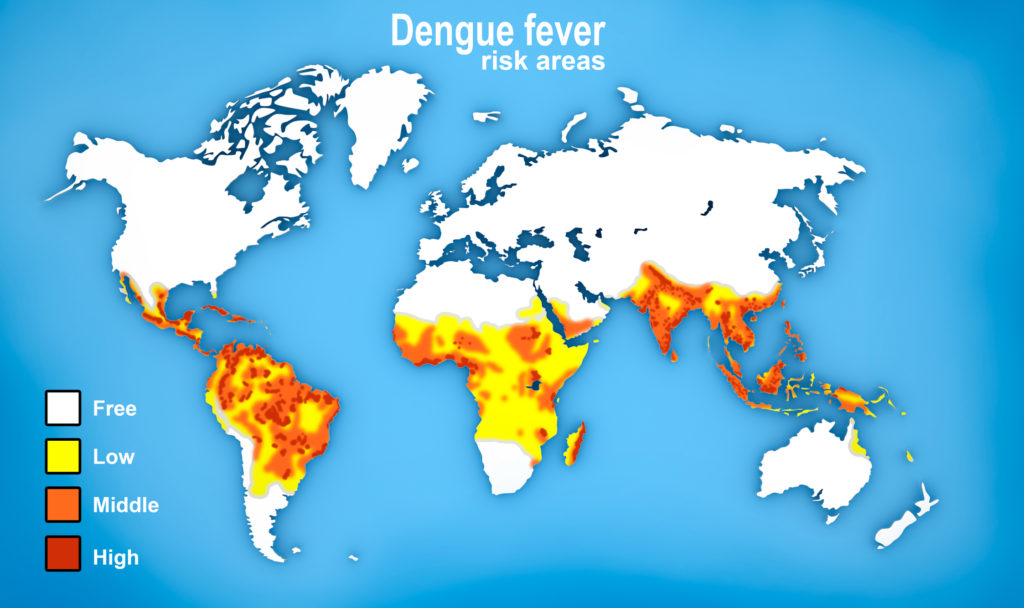

Dengue fever is a viral infection most prominent in Earth’s tropical regions.

According to the World Health Organization global incidence of dengue has exploded in recent years, cases multiplying thirty-fold over the past fifty years. 390 million infections occur annually while a quarter of those develop serious symptoms and twenty thousand die.

There are five distinct serotypes (basically, strains) of the virus, known scientifically as DEN 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. The fifth serotype has only recently been identified. Recovery from one strain of dengue offers lifelong immunity, but only for that particular strain. Subsequent infections by other strains actually increase the chances of it developing into severe dengue.

Basically, try not to get dengue fever. And definitely don’t get it a second time!

In America dengue is classified as “very rare”, although Puerto Rico deals with thousands of cases annually.

Dengue is closely associated with two other viral diseases, Zika and chikungunya. The same species mosquito transmits all three and they share many overlapping symptoms. In fact, it can be difficult to differentiate one from another.

Dengue fever transmission

Transmission occurs by way of female Aedes mosquitos. The mosquito becomes infected when it bites a person with the dengue virus in their blood.

The crazy thing about the Aedes mosquitoes which transmit dengue? They feed during the daytime. Unlike their annoying malaria-transmitting Anopheles cousins you’re used to dealing with solely in the evening, these guys will get you at sunrise as well.

This intriguing piece in The Atlantic details the study and potential viability of an appetite-suppressing drug which may prevent mosquitoes from biting humans in the first place. It is well worth a read.

Human to human transmission can occur, but not via casual means. Blood transfusions and organ donation may transmit the virus, but other bodily fluids will not.

Speaking of blood, a dengue fever infection will prevent a person from donating blood for a period of time. Restrictions are all over the map, but the American Red Cross advises a six month wait.

Dengue fever symptoms

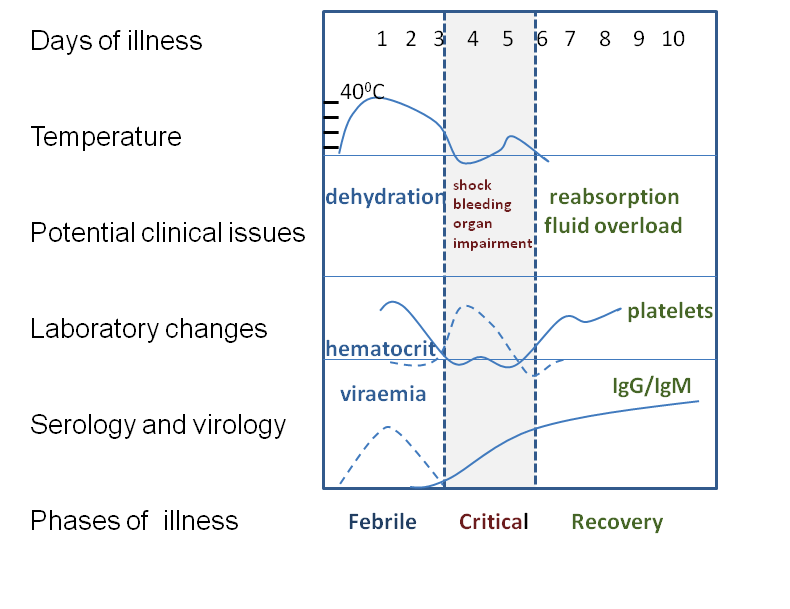

Dengue has an incubation period of 4-10 days. That means symptoms don’t manifest until several days after a person is bitten by a carrying mosquito. Because of this it’s often difficult to pinpoint when and where an infection occurred.

As far as symptoms, they typically mirror a severe case of the flu, last for 2 to 7 days and include the following —

- High fever (104℉/40℃)

- Severe headache

- Nausea/vomiting

- Joint pain

- Pain behind the eyes

- Skin rash

Dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF, and often simply “severe dengue”) is a potentially deadly complication due to fluid accumulation, plasma leakage, bleeding, respiratory issues and organ impairment. When the WHO says 20,000 people die from dengue, this is how it happens —

- Persistent vomiting

- Severe abdominal pain

- Rapid, shallow breathing

- Blood in the vomit

- Bleeding gums

- Restlessness

Based on WHO guidelines, the chart below shows the course of a dengue fever infection.

Dengue fever treatment & prevention

Standard treatment for dengue fever includes paracetamol to lower fever and ease joint pain, plenty of rest and lots of fluids. The latter may include intravenous fluids in a hospital setting. Aspirin is a big no-no as it inhibits blood from clotting.

There is no magic bullet for dengue fever, although a vaccine is just beginning to hit the market.

But…

“The analysis confirmed that Dengvaxia provides persistent (protective) benefit against dengue fever in those who had prior infection. For those not previously infected by dengue virus, however, the analysis found that in the longer term, more cases of severe disease could occur following vaccination upon a subsequent dengue infection.”

This quote is from Sanofi, the maker of the vaccine. So getting the vaccine could make a dengue infection worse? Comforting news.

That revelation caused the Philippines, unsurprisingly, to halt a massive vaccination program.

Current advice is for those who have yet to be infected with dengue skip the vaccine. For people with a prior infection under their belt, get the vaccine.

For most travelers, standard mosquito bite prevention is key.

I am a big fan of sunscreen/insect repellant combo spray. One less bottle for my backpack!

Of course you need to remember to actually use it. That was my downfall. The mosquito repellant became an afterthought and I recall using the spray only for sun protection. I was probably bitten early in the day when I didn’t think I needed sun protection.

Lesson learned.

Dengue fever long-term effects

Recovering from dengue fever is not necessarily a quick proposition. Most people are back to themselves within a couple of weeks, but every person is different. There are numerous accounts of travelers dealing with the lingering effects for weeks and months after the initial infection. They include —

- Lethargy

- A rash which peels like a rattlesnake

- Hair loss

DO IT YOURSELF

Banyuwangi

Kawah Ijen lies at the eastern tip of the island of Java, not far from the city of Banyuwangi.

Getting There and Around

Independent travelers can visit Banyuwangi via bus, train, private vehicle or tour.

I almost always prefer the train and this region of Indonesia is no different. Plus the internet is rife with tales of ripped-off tourists, transportation cartels and generally less than pleasant bus experiences. Google public transportation Mount Bromo for a taste.

The train passes lovely rice fields and beautiful countryside while avoiding the touts and variable ticket pricing of the bus.

Traveling west to east, the train connects Surabaya, Probolinggo (depart for Mount Bromo) and Banyuwangi. In theory one could travel the entire 1200 km length of Java by rail.

Check out Seat 61 for all the relevant details.

A 24-hour ferry connects Bali (Gilimanuk) with Java (Ketapang, the port just north of Banyuwangi). Service operates every 30 minutes in each direction. The crossing takes about 45 minutes and tickets cost IDR 8,000 (US$0.56).

Speaking of Bali, the number of brief tours which depart Bali and call in at Kawah Ijen are too numerous to mention. Any hostel, guesthouse or hotel will have recommendations.

There are a lot of young backpacker groups doing these tours. I read somewhere Kawah Ijen sees up to 2,500 visitors per night in high season! Things were busy the night I hiked up, but that number seems stunning. Then again, I was half delirious, so don’t take my word for it.

Direct flights to Banyuwangi (BWX) are available from Jakarta (CGK) and Surabaya (SUB). Connecting service links many other cities including Semarang (SRG) and Denpasar (DPS).

Sleeping

I stayed at Kampung Osing Inn. I booked my stay one day in advance and didn’t exactly have my choice of accommodation. Don’t expect anything resembling luxury. The rooms are B-A-S-I-C. Simple breakfast included.

But I have to give the place credit for coming through when I needed assistance. The guesthouse manager drove me on his motorbike to get the supplies from earlier in the story. He phoned around and set up my minibus to Bali. Their Ijen tour didn’t cut any corners.

Kawah Ijen

Ijen lies about an hour northwest of Banyuwangi. Good roads and proximity to Bali mean it’s a relatively popular destination, especially with young tour groups. If you think you will be alone at Kawah Ijen, think again.

Don’t even consider visiting Ijen without a guide. The acidic lake is so corrosive it can dissolve metal and the wafting, toxic fumes are widespread inside the caldera (or so I read!).

And occasionally outside the caldera too.

In theory the mine area is off-limits to visitors, but you know how people can be. Visitors have died on Ijen’s slopes. The only deterrent is a sign.

Former miners lead many independent trips up Kawah Ijen. Utilizing a former miner as a guide benefits the local community and will give you a better insight into the entire experience. Plus it’s good value. I paid IDR 420,000 (US$29) at the time and the entire trip ran close to eight hours.

Blue flame tours depart after midnight and return around breakfast. Daytime tours run as well, though the blue flame isn’t visible in daylight. And it isn’t guaranteed at night either. A high quality tour will provide a gas mask. Consider bringing along a bandana or sarong.

And don’t forget the mosquito repellant.

Pingback: Klotok | Borneo | Indonesia | Kalimantan | Orangutans | No Guidebooks